A group of women seated with their babies are giving their full attention to Mama Elisabeth Muganwa in a large plastic tent in Kikumbe, an internally displaced persons (IDP) camp just 20 kilometres outside Kalémie, in the Tanganyika region of the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.

“Hello women,” Muganwa calls out, and the mothers respond in kind. “Today we are going to show you how to prepare baby food that is nutritious and delicious from what is grown around here.”

She speaks while arranging various bowls around a small pile of hot coals, preparing the women for a cooking demonstration, tailored to their needs.

This way of teaching food preparation is a new concept here at Kikumbe camp in the fight against malnutrition. UN figures for 2021 indicate that in the Tanganyika region alone, more than 40 percent of the population is at food crisis level, meaning that people are living with high levels of acute malnutrition.

The majority of the inhabitants are Bantu people who have fled intermittent intra-communal fighting with the Batwa community since 2015. The movement between their homes and the camp has had an affect on the levels of malnutrition.

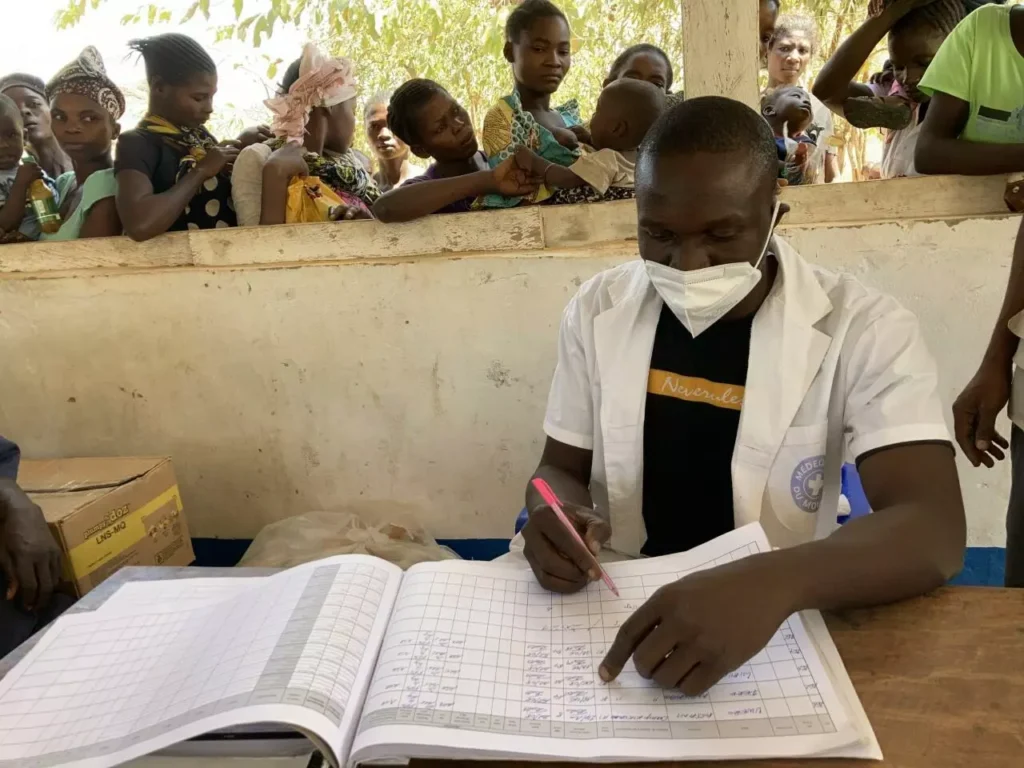

And reality is just a five-minute walk from the cooking demonstration. On the other side of the camp, Celestin Mutindi, a nurse practitioner, has his hands full with the 200 mothers and babies waiting to be seen by him to measure malnutrition levels in their infants.

A healthcare worker strike in the Congo has tripled his work, as well.

Mutindi attends to Fatuma Kinyongo and her baby Richard by measuring his arm with a paper that indicates whether he is underweight for his age.

“He is not malnourished, but we’re giving her a 30-day supply of Plumpy Plus to reinforce his health,” says Mutindi, speaking of the enriched baby food with a base of peanuts that has been proven to help undernourished babies gain weight.

Better baby nutrition

Back in the tent, the cooking demonstration is in full swing, as instructor Muganwa explains the way to make a home-grown version of nutritious baby food, that also has a peanut base.

“Mama sante!” Muganwa calls out between instructions.

“Mama sante!” the mothers respond in French, or, ‘women’s health’.

While toasting a pot containing peanuts over the coals, she hands them off to her assistant Sakina Lukombe, who mashes them with a large mortar and pestle, typically used to mash cassava.

The mashed peanuts are brought back to the pan and are boiled for up to five minutes, as Muganwa stirs consistently to avoid lumps.

“Next, three soup spoons of maize flour,” says Muganwa, who continues to stir the mixture for 15 minutes as it becomes less soupy, and thicker, like baby food.

3 tbs maize flour

1.5 tbs creamy peanut butter*

1 tsp sugar

Pinch of salt

Water

Mashed banana for garnish, if desired

Pour one cup of cold water into a pot on medium heat. Add peanut butter and stir.

Let it boil for 3 to 5 minutes. Add the flour to the pot, but continue to stir for 15 minutes to avoid clumps.

Lower the heat and spoon the amount of baby food needed into a clean bowl.

Add the sugar and salt, and mashed banana (if desired).

The baby food should be semi-solid, not semi-liquid.

*peanut butter for ease of use instead of mashing peanuts into a paste

Muganwa was trained by Friends of People in Distress (APEDE), a local NGO, on how to prepare the meal for infants between the ages of six months to one year. A mother of six herself, she says that although the baby food is made of six ingredients found in the camp or grown there, she didn’t realize they could be put together in this way.

“We farm all these different things, like peanuts and maize, but often we don’t know how to mix it together,” says Muganwa.

The UN estimates that malnutrition is acute in Katanga, the region Kikumbe camp is located in. Many who were interviewed for this article said they only eat one meal a day.

In an effort to lower rates of malnutrition, local NGO APEDE, the World Food Program and other partners working in the area went door-to-door to survey mothers about what they cooked for their families and especially for their infants.

With the help of nutritionists, a recipe book was created that took into account the way the mothers prepared food and made small changes in order to boost nutrition but only using ingredients that were in the camp or easy to obtain.

Cassava flour, a staple in Kikumbe, is nutrient-poor, especially for babies, says nutritionist Laure Kabeya of APEDE.

“Cassava flour is not good for digestion, that’s why they should use maize flour, which has more nutrients and some protein,” she says.

“It’s light and easy to digest for a baby–they absorb it better,” she says, adding, “we did this cooking demo to change the way moms feed their babies.”

“Mama afiya!” Muganwa calls out while stirring the maize flour in.

“Mama afiya!” ‘Women’s good health’ in Swahili, the mothers respond.

Muganwa adds a pinch of iodized salt and a teaspoon of sugar before spooning the hot baby food into bowls for the mothers to give to their babies.

The hot porridge is a hit. The number of babies crying during the cooking demonstration seem to like their new food, and the mothers, who are blowing on it and tasting whether it is the right temperature, enjoy the taste, too.

Veronique Maoua with her son, Bert, said she was going to fix this for him—he liked it a lot.

“After watching the cooking demonstration, the baby food will build Bert and make him healthier. It will help him,” she adds.