Anytime there’s a pest infestation in my house, I waste no time looking for ways to exterminate them. It’s my house, animals should stay in their place. But then, there’s always this sarcastic voice in my head that reminds me that before the space became my home, I cut down the trees they lived in, levelled the shrubs that fed them, colonised their habitat, and then concreted it off. It reminds me that, even biblically, I came last. I met them here.

One of my genuine hopes is that one day, humans sit down and try to understand how harmful we are to the environment. How we take, take, take, and rarely give back. Human carcasses lie dainty in non-biodegradable coffins, while animals die and supply nutrients to the earth. They feed back to nature with their dung; we hide ours in sealed-off pits. In the same way, we mess up the air and leave trees to clean it up, then go ahead and chop them off.

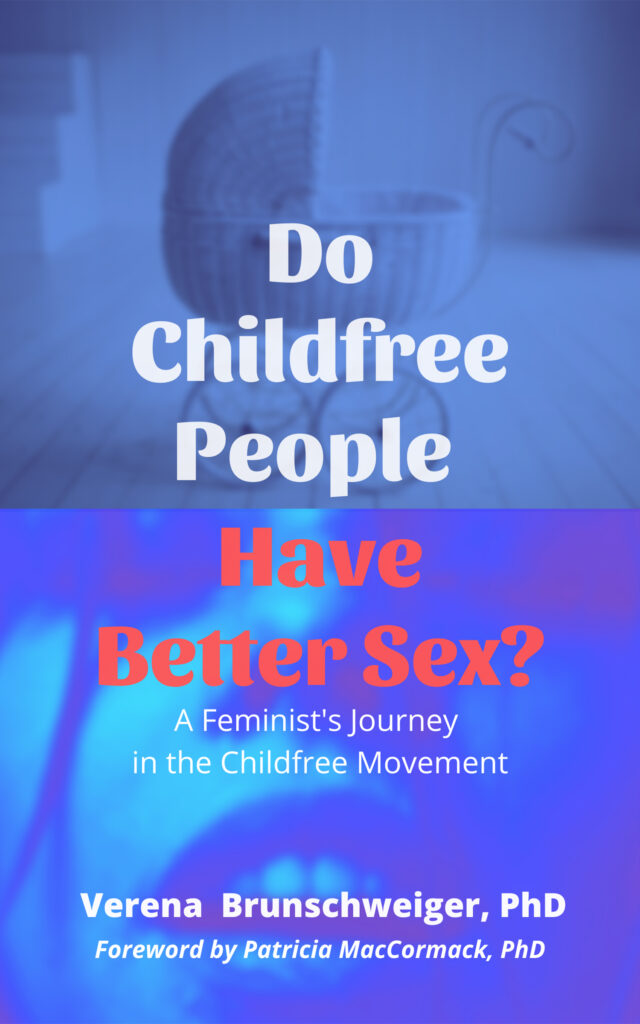

Till I read Dr Verena Brunschweiger‘s Do Childfree People Have Better Sex? I never clearly captured childbirth as arguably the greatest facilitator of climate change and other chaos currently besieging the earth. Dr Brunschweiger’s book intelligently painted this idea into something I can simply summarise as this sentence: more people means more digging into nature’s finite goodybox, and consequently more conflict for these resources.

Do Childfree People Have Better Sex? is an indictment of the reproductive culture of humans that has gone unquestioned for a long time. Why do we have children? What really is the benefit for us as parents? How is it beneficial to children that they are born, especially in a world going bonkers? Do these benefits outweigh the costs, both individually and on the larger scale of society?

With this statistically backed piece, Dr Brunschweiger tackles human reproduction as a concept on four levels of explanation: ecology, feminism, politics and the philosophy of anti-natalism.

In terms of politics, Dr Brunschweiger draws a connection between right-wing extremism and the aggressive campaign to continue birthing. The crazy need to populate the world with your own kind in the name of nationalism,

Philosophically, the writer does a perfect job of providing a naked picture of just how cruel and unfair it is that we experience the human condition, (life and death with suffering sandwiched in-between), then go ahead to force others to experience it with us. One of the most beautiful things that can happen to a human being is to not exist. To never feel the smarts of pain, the pangs of hunger, the grill of grief. To exist is to suffer, to mete out suffering; to die and kill. But for our own selfish needs to put our “stamp” on the world, or have insurance for old age, or the more illogical one of just obeying the societal imperative, we continue having children.

In addition, the writer expresses an uncommon empathy towards the plight of animals in a society where they are regarded as living beings unworthy of rights. The indiscriminate use of animals (for food, recreation, luxury, and so on) by humans is creating a deficit in this ecosystem where balance is critical. It gets even worse in our relationship with plants and trees. It is almost as if the world is getting hungrier for paper and furniture even as temperatures continue to leap.

The common advice to tackle climate change is to eat less meat, reuse your plastic, board more public transport, and so on. But we’re not going to pretend the greatest contributors to pollution are not industries.

Thus, how much can our metal-straw lifestyles really do if corporations continue producing and, in the process, releasing toxic gases and wastes into our atmosphere?

But companies aren’t digging into earth’s resources to manufacture products for ghosts. Their expansions are not due to an influx of aliens into the earth. We, humans, create demands and drive up the supply of products that result in earth-damaging waste as we continue to procreate. A truly vicious cycle.

The book also draws out the fact that the idea of being child-free stems from the freedoms that feminism has gifted women. Isn’t it unlikely that we’d have women today who can choose not to have children if we didn’t believe that women are as equal as men, with agency over their bodies and the freedom to choose what they want to do with them? Also, the contrast between child-free women and moms shows how pregnancy, childbirth, and childcare bite women in the back. A mother is often regarded as a deity in society, but at what cost? Body changes that are sometimes irreversible (closely accompanied by the strain of society’s determination to fit all women into a body size), delays to women’s advancement, educationally, financially, and professionally, are all effects of reproduction that women often have to bear alone.

Back to the initial question: Do Child-free People Have Better Sex? Once again, Dr. Brunschweiger dips into facts and research, and you can’t but reach the conclusion that it’s a possibility that sex life goes to naught after children (Don’t take my word for it, read the book). And it’s not just sex life, it’s sleep, finance, relationships, career, and just general wellbeing, especially for women who do the heavy lifting.

One reservation I had with this book was the finger-pointing for those who are also in this fight to save the planet, most notably, Greta Thunberg. I understand that she might not be squarely on the same page with the writer on the ideals of climate activism, but it is undeniable that this girl is forcing leaders to take notice of the problem. To write about her and other young activists just as “teenagers posting sentimental stories” or comparing them to academic heavyweights like Jonathan Frazen and Matt McGrath, does not do justice to their global impact. I did not find this critique of these youngsters necessary at all, because, in the end, the problem of climate change has to be attacked from all angles possible. We need all the hands possible to get more people on board and create a significant impact. The rhetoric of these youngsters resonates with a demographic and speaks to the attention of a set of people. They also deserve to be listened to.

In addition, I find a recurring motif of monolithism in the portrayal of feminism. For example, saying “Feminists don’t watch porn,” or that feminists who don’t see motherhood as a cage of patriarchy and do not actively seek to destroy the construct, practice “pseudo-feminism” all seem to portray a sense of ‘this and only this is how feminism should be.’ This is arguable. We cannot force what we think should be “the” explanation on people. My brand of feminism will be very different from that of a woman in Pakistan or Sweden. While we fundamentally demand equal dignity for women, like every other human being, how we’ve been undignified by our various societies, and our experiences or how we relate to these things are different. I also believe feminism is a journey of learning and unlearning, and the fact that one feminist is not at the level of knowledge another is does not make them less of a feminist.

I had the privilege of speaking with Dr Brunschweiger about the idea that motherhood is anti-feminist. She said, quoting Shulamith Firestone in her answer:

“The heart of women’s oppression is her childbearing and child-rearing role.” I couldn’t agree more. It’s exactly what I want to express. No mum-bashing but saving women who still have a chance to stay independent, as female autonomy is so important in today’s world.

“Second-wave, “real”, radical feminism rejects the mother role. There are some mothers who’d say they’re feminists, as they campaign against prostitution, and so on, but they are liberal/postmodern/third-or fourth-wave feminists, not radical ones, as this concept, which is also mine, considers motherhood as the patriarchal imperative,” Dr Brunschweiger says.

I partly agree with her on this. However, how about those feminists who want to be a mother on their own terms? Those who genuinely desire to nurture and parent their children in the way they want to. It is also worthy of note that there are a lot of women who are mothers today and fit into none of the patriarchy’s nonsense of what a mother should be. In other words, motherhood exists outside of the box for them. I don’t think a dichotomy of us-versus-them should be created. We all really want the same thing at the core: a better and more dignified life for women.

While writing the review, I kept wondering how I, as someone who had never had a child, could understand the feelings parents have for their children. Love is a brand of madness. It consistently defies sense. In fact, it should not be logical. In the wise words of Taylor Swift, “Don’t blame me, love made me crazy; if you’re not, then you ain’t doing it right.” Most of the time, love is defined only by the sensitivities of the people who inhabit the emotion for the duration of its currency. At best, I can only empathise. Thus, whenever I am confused as to the continued craze about having kids, I just recess and remember the fact that I can barely judge because I have no inkling of how it feels.

It will honestly be difficult for most of us, whose entire existence has been tied to re-existing and procreation, to go through this book. It has to be read with an utterly open mind, a mind ready to question every single thing they’ve learnt about being a human with the divinely imposed duty of reproducing. While I wish the book had been a tad less stark in its honesty or presented as a little easier pill to be swallowed by many, I also think it is the necessary shock pad humans need in these critical times.

Our continued reproduction will only lead to more depletion of nature’s resources, and by extension, result in several conflicts for these resources, the evidence of which we are already seeing.